18 Monitor for Sex Effects

Generally, as was the case for our initial critique, we would proceed by inspecting warnings from the Experiment node, first.

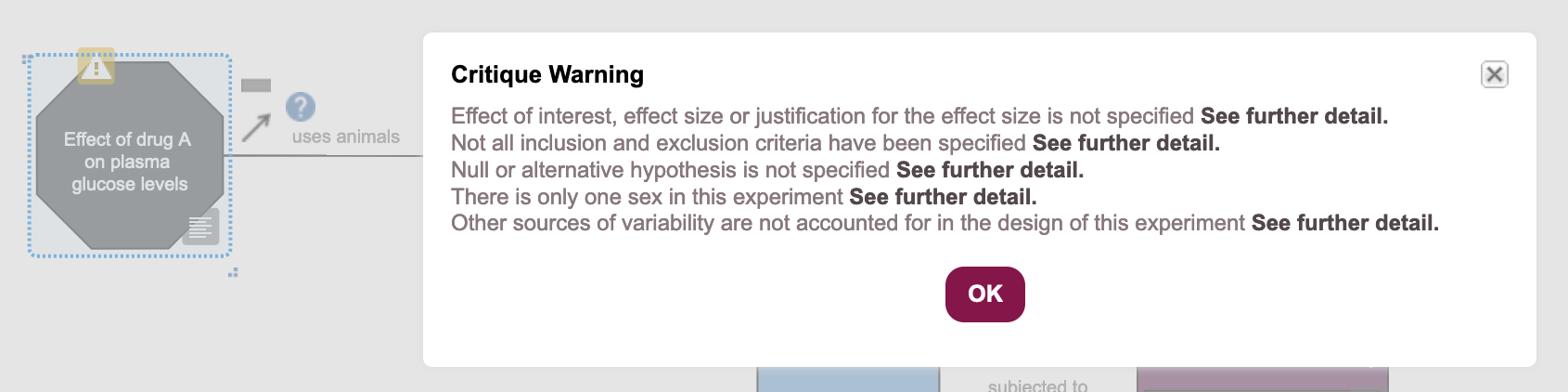

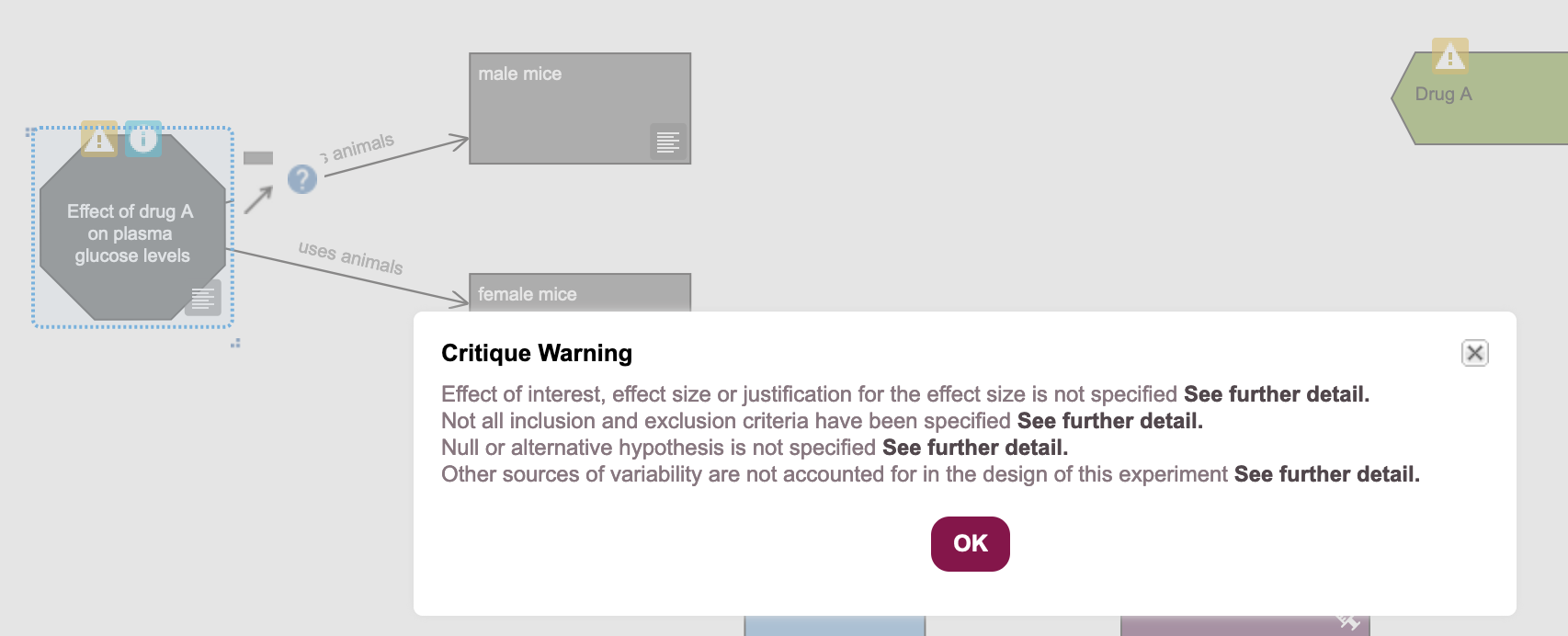

- Click on the yellow Warning icon, on the Experiment node to bring up the critique warnings (Figure 18.1)

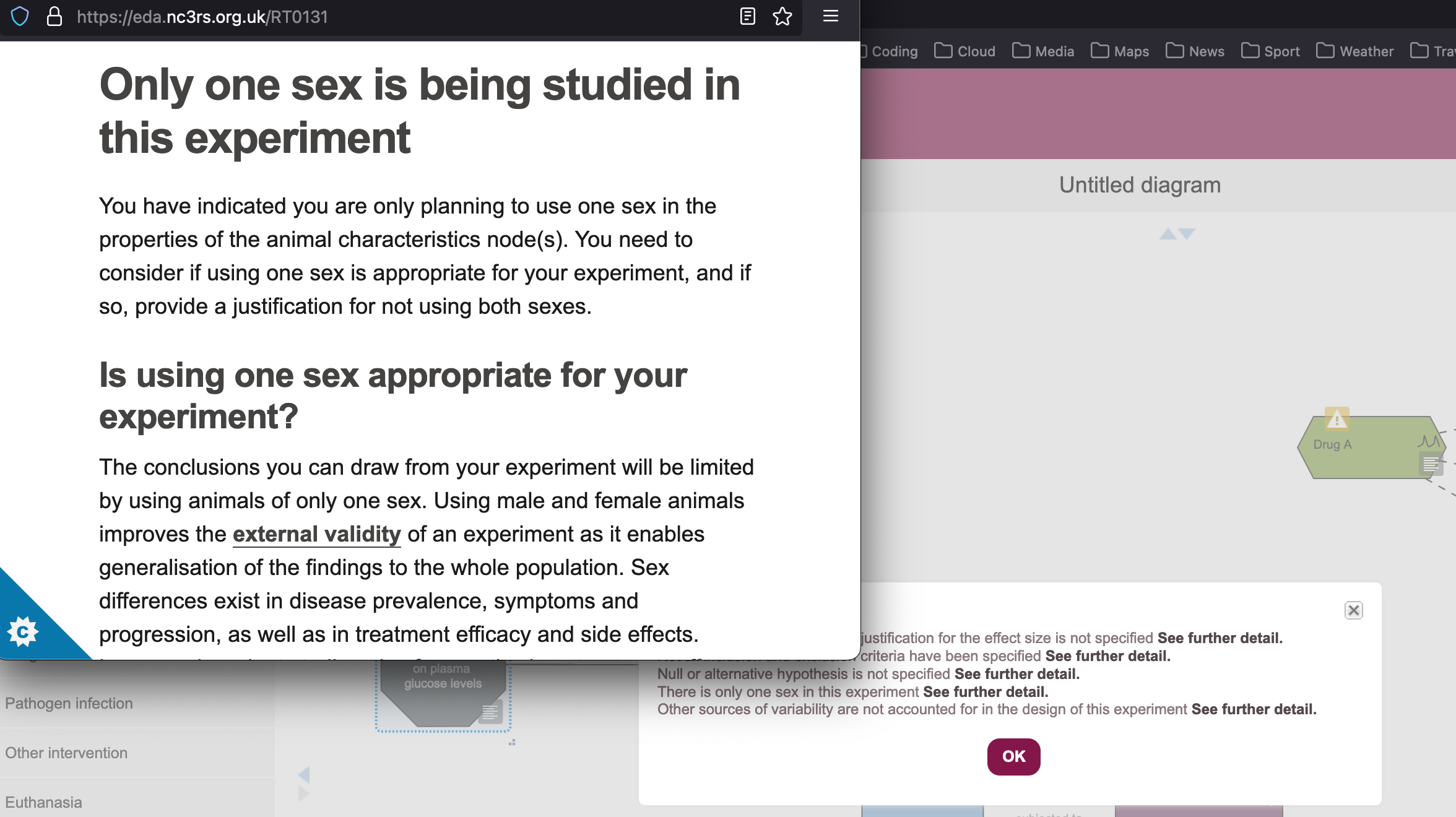

- Click on the See further detail link to bring up information about this warning (Figure 18.2)

- Close the help popup window, and click on the

OKbutton to dismiss the dialog box.

We are taking the definitions of these words to mean:

- Sex: a set of biological attributes in humans and animals that are associated with physical and physiological features including chromosomes, gene expression, hormone function and reproductive/sexual anatomy

- Gender: the socially constructed roles, behaviours and identities of female, male and gender-diverse people

If our research designs do not take sex and gender into account, the evidence we generate may be incomplete or simply incorrect; we risk not only doing harm (such as extrapolating findings based on male samples to females), but also missing critical opportunities to improve health (for example, not detecting the benefits of an intervention in a subgroup of men). 1

When we described the initial design of this experiment (Chapter 12), we stated that we were not going to consider the effect of subject sex on drug efficacy:

Mice will be randomly assigned to receive either drug A or vehicle only without regard to the sex of the animal.

And, when we laid out our beliefs about the experiment, we were more explicit, noting that:

- We are not testing for the effect of sex on drug performance as an experimental variable of interest

- We are also not monitoring for the effect of sex on drug performance as a nuisance factor

However, as experimenters, we do not necessarily get the final say in whether we use one sex or both sexes.

18.1 Expectations about sex in experimental design.

As part of a community-wide drive including funders, researchers, and authoritative bodies, to explicitly consider diversity in research design, there is an increased emphasis on ensuring that research includes all groups that have the potential to benefit from its findings. This is particularly a concern of the Medical Research Council (MRC), which funds medical research in the UK. Failure to account for sex in experimental design may lead to a study not being funded.

This applies to all animal, cell, tissue, and human participant research.

Categories to be considered include sex, gender, ethnicity, age, socio-economic status, and disability.

Of particular importance in animal studies is the requirement for both sexes to be used in experimental design.

MRC requires applicants to embed diversity in the design of their studies (see MRC’s policy on embedding diversity in research design). This includes the requirement for both sexes to be used in the experimental design of grant applications involving animals, and human and animal tissues and cells, unless there is a strong justification for not doing so.

We also expect applications to include information about the sex of the animals used in experiments, as well as the sex of studied tissues and cells. If you don’t know the sex of the cells and tissues you use, you should plan to determine it as part of your research.

Use of both sexes is the default

It is still possible to obtain funding from the MRC for single-sex studies, but only where there is strong justification for doing so. There are a number of possible justifications, including:

- where there are acutely scarce resources (for example, human tissue samples of rare diseases)

- research into the mechanisms of purely molecular interactions (for example, when investigating protein-protein interactions)

- single-sex mechanisms or diseases (for example, ovarian cancer)

- logistical or ethical considerations with robust justification.

Attempted justifications for single-sex designs that the MRC considers to be insufficient include:

- female variability (in most cases)

- prior work was performed in only one sex

- a lack of evidence of sex having an effect

As noted in Chapter 17, even experienced scientists with many publications and long track records of research funding may never have received any formal training in experimental design. This can lead to entrenched and outdated ideas being propagated, such as that it is not necessary to use both sexes in an experiment because it was previously shown that there is no effect due to sex 2.

Ultimately, as a researcher you are responsible for the rigour and ethics of your own actions. It is always advisable to consult with funding bodies and specialists in research ethics, rather than trust the word of senior scientists alone.

18.1.1 Common statistical misunderstandings

It is still possible to hear scientists argue that they should not use both sexes in their experimental design, because it would double the number of animals required, and this would go against the 3Rs principles. A 2021 study also found:

Using a list of […] published articles […] we examined reports of sex differences and non-differences across nine biological disciplines. Sex differences were claimed in the majority of the 147 articles we analyzed; however, statistical evidence supporting those differences was often missing. For example, when a sex-specific effect of a manipulation was claimed, authors usually had not tested statistically whether females and males responded differently.

and called for further efforts to “train researchers how to test for and report sex differences in order to promote rigour and reproducibility in biomedical research” (Garcia-Sifuentes and Maney (2021)).

In addition to experimental design, it is possible that even experienced scientists with many publications and long track records of research funding may never have received any formal training in statistics. 3

Again, as a researcher you are responsible for the rigour and ethics of your own actions. It is always advisable to consult with statisticians, rather than trust the word of senior scientists alone.

Changing the design of an experiment from single-sex to two sexes typically does not require an increase in the number of individuals studied. It can often be achieved by running the same experiment but changing half the animals to the opposite sex (e.g. a study designed with 8 males becomes a study with 4 males and 4 females), and analysing the results using ANOVA instead of a t-test.

One reason the common misunderstanding that animal numbers need to be doubled arises is because researchers don’t immediately realise that sex can be considered as a blocking factor (also known as a nuisance variable), rather than a main effect of study.

This is important because, when we estimate the count of sample size needed by power calculation, we are considering the number of individuals required to establish a result only for main effects. We do not need to power experiments for a statistical difference in nuisance variables. Consequently, if the main effects (independent variables of interest, in EDA) remain the same, the number of individuals required to power the experiment remains the same.

Considering sex as a blocking factor in this way is known as “monitoring for a difference in sex.” We do not have differences between sexes as a focus of our study, but we would like to be in a position to notice, if there is a large difference between the sexes.

18.2 Modify the experimental design

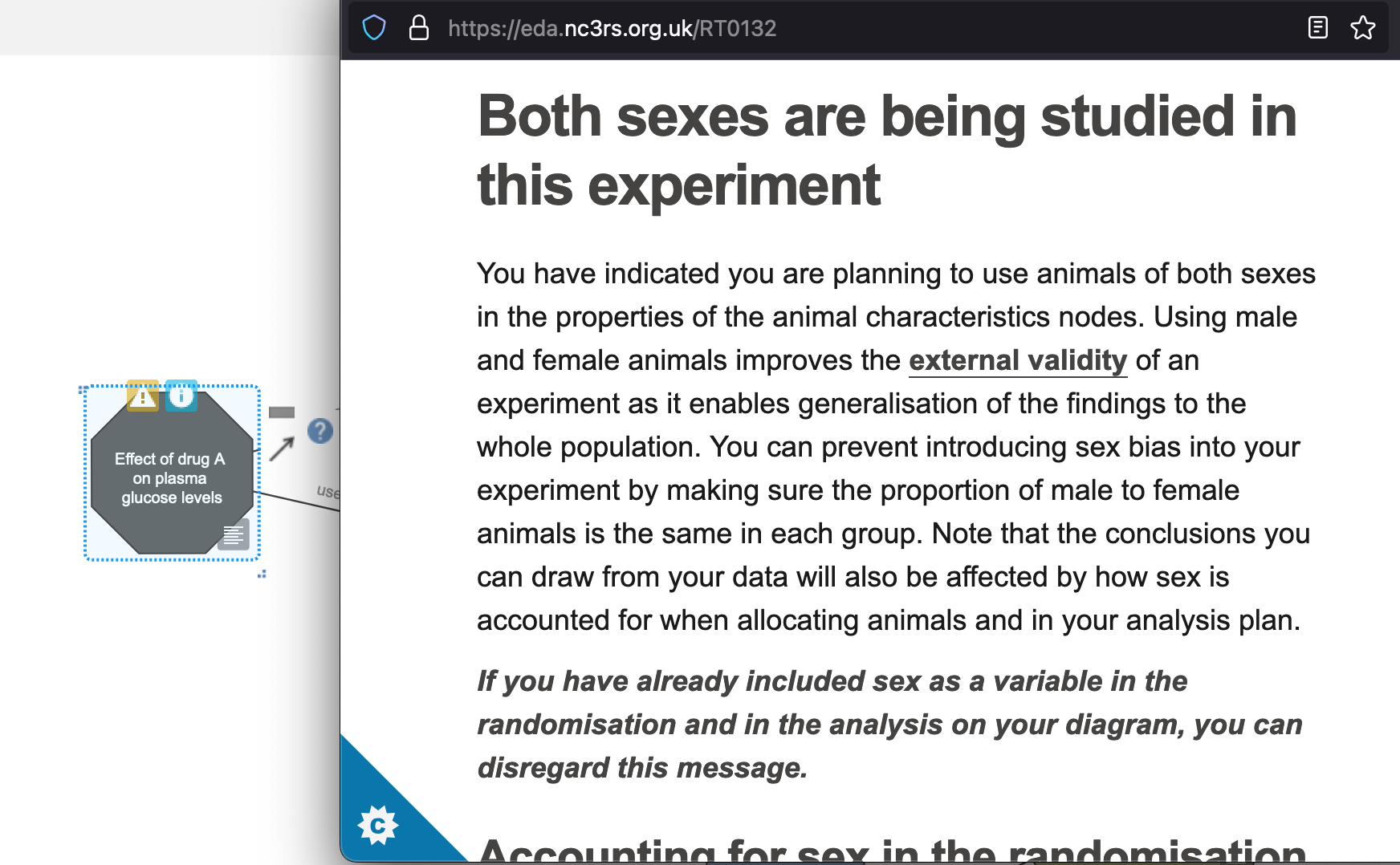

Our experiment is looking at glucose concentration in plasma, so there is not a reasonable justification to exclude female mice from the design. In order to update our experimental design to accommodate both sexes, we need to do two things:

- Add an Animal characteristics node, so that we have one Animal characteristics node for male mice, and one for female mice

- Add a Nuisance variable node representing the sex of individual subjects, linking this to our Allocation node, to indicate that we will account for sex in the allocation to experimental groups, and to our Analysis node, indicating that we will use sex as an explantory factor in our statistical analysis.

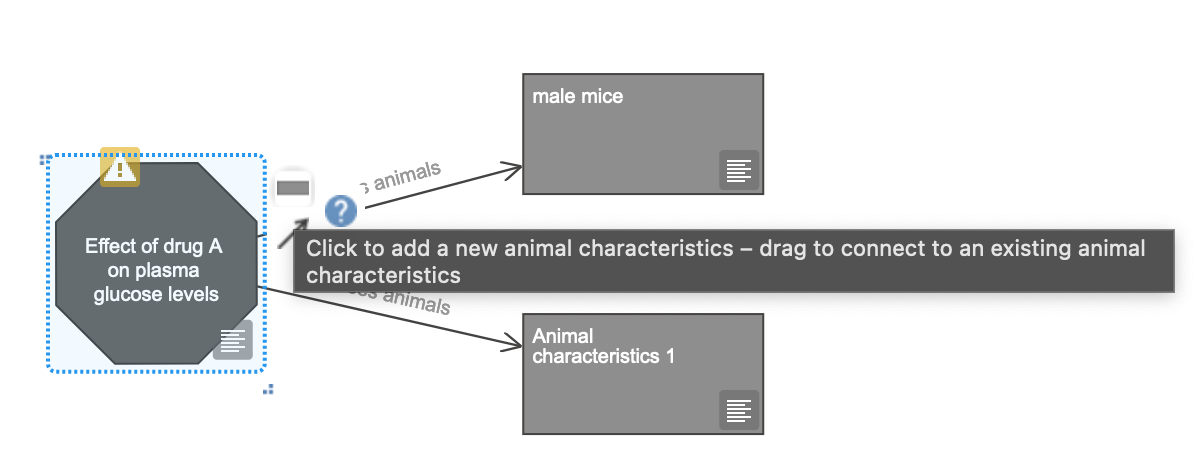

18.2.1 Add an Animal characteristic node for female mice

- Click on the grey box in the Experiment node icon panel, to create a new Animal characteristics node (Figure 18.3)

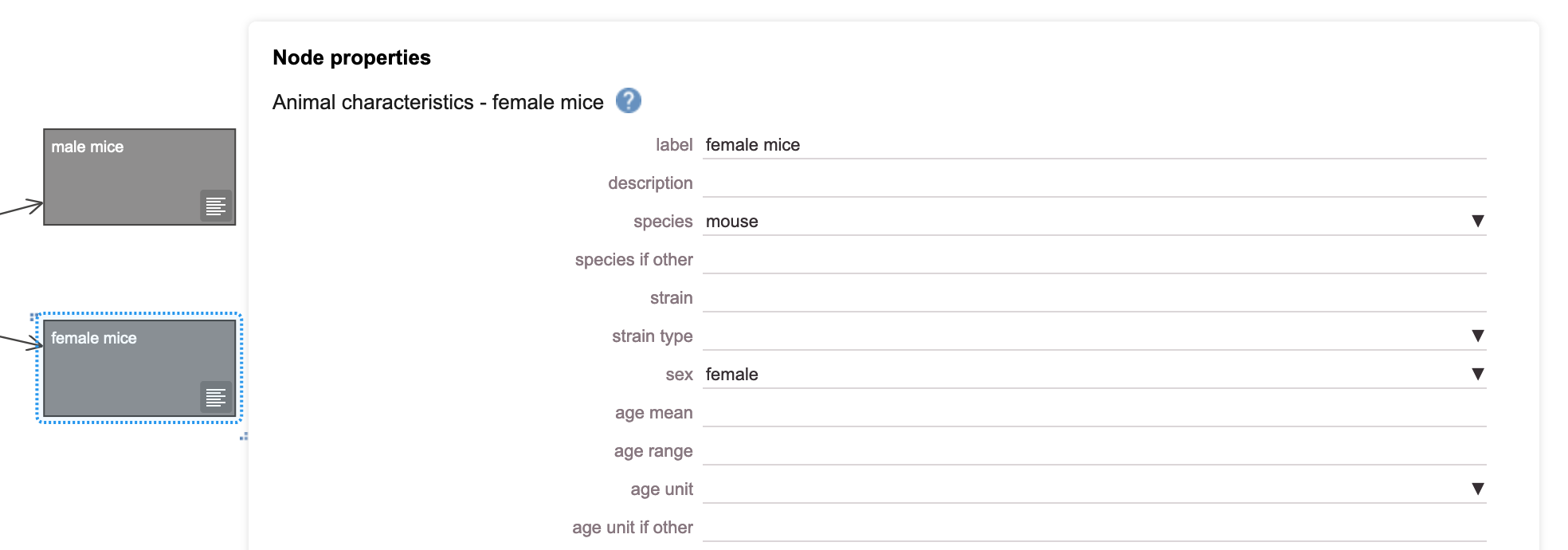

- Click on the Node properties icon of the new Animal characteristics node, rename the label field to “female mice”, change the species field to “mouse”, and change the sex field to “female” (Figure 18.4). Click on

Closeto dismiss the dialogue box.

18.2.2 Rerun the Critique tool

- Use the

Toolsmenu and click onTools -> Critique - Read the critique output, then click on the

OKbutton to close.

- Click on the yellow Warning icon, on the Experiment node to read the critique warnings (Figure 18.6). Note that the warning about using only one sex is no longer present. Click on See further detail next to the “Other sources of variability…” warning, to note that EDA warns us that the diagram does not include nuisance variables. Close the help window, and click

OKto dismiss the dialogue box.

- Click on the new blue Advice icon, on the Experiment node to bring up the popup help window (Figure 18.7). Note that this advises us to use sex as a variable in both the randomisation and the analysis for this experiment, then close the help window.

18.2.3 Add sex as a Nuisance variable

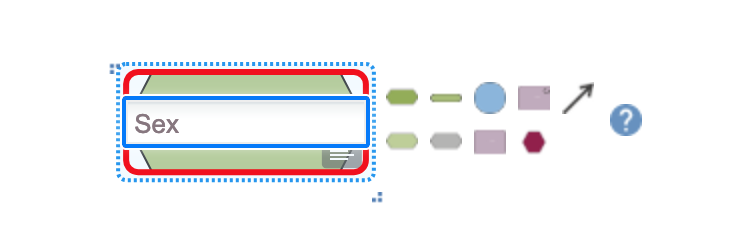

- Drag a Nuisance variable node from the sidebar on the left, onto the canvas, and rename it as “Sex” (Figure 18.8).

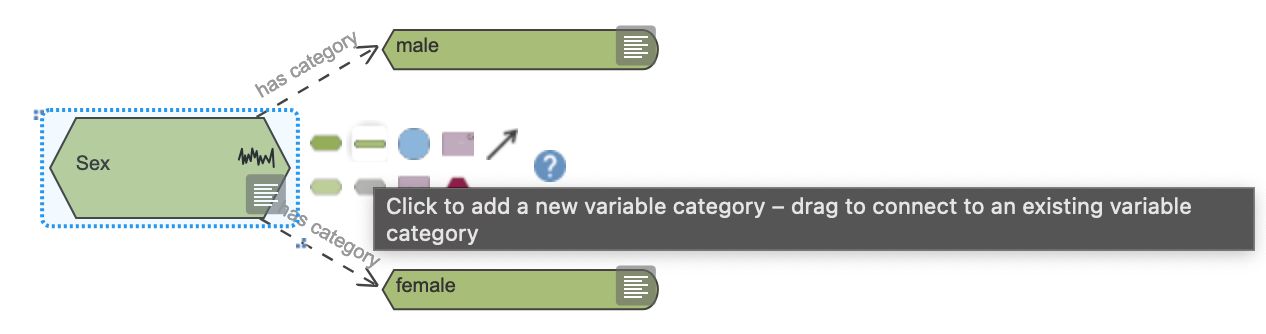

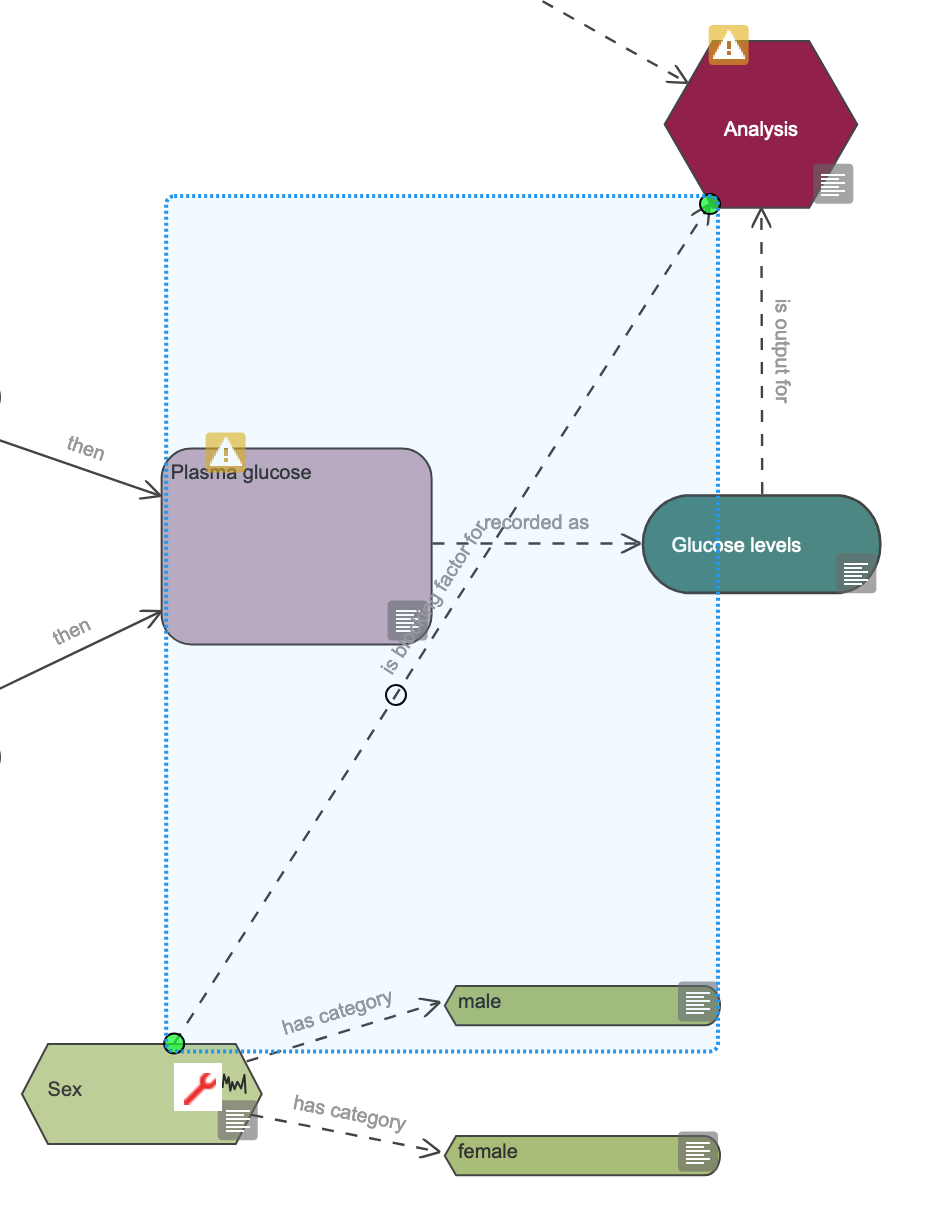

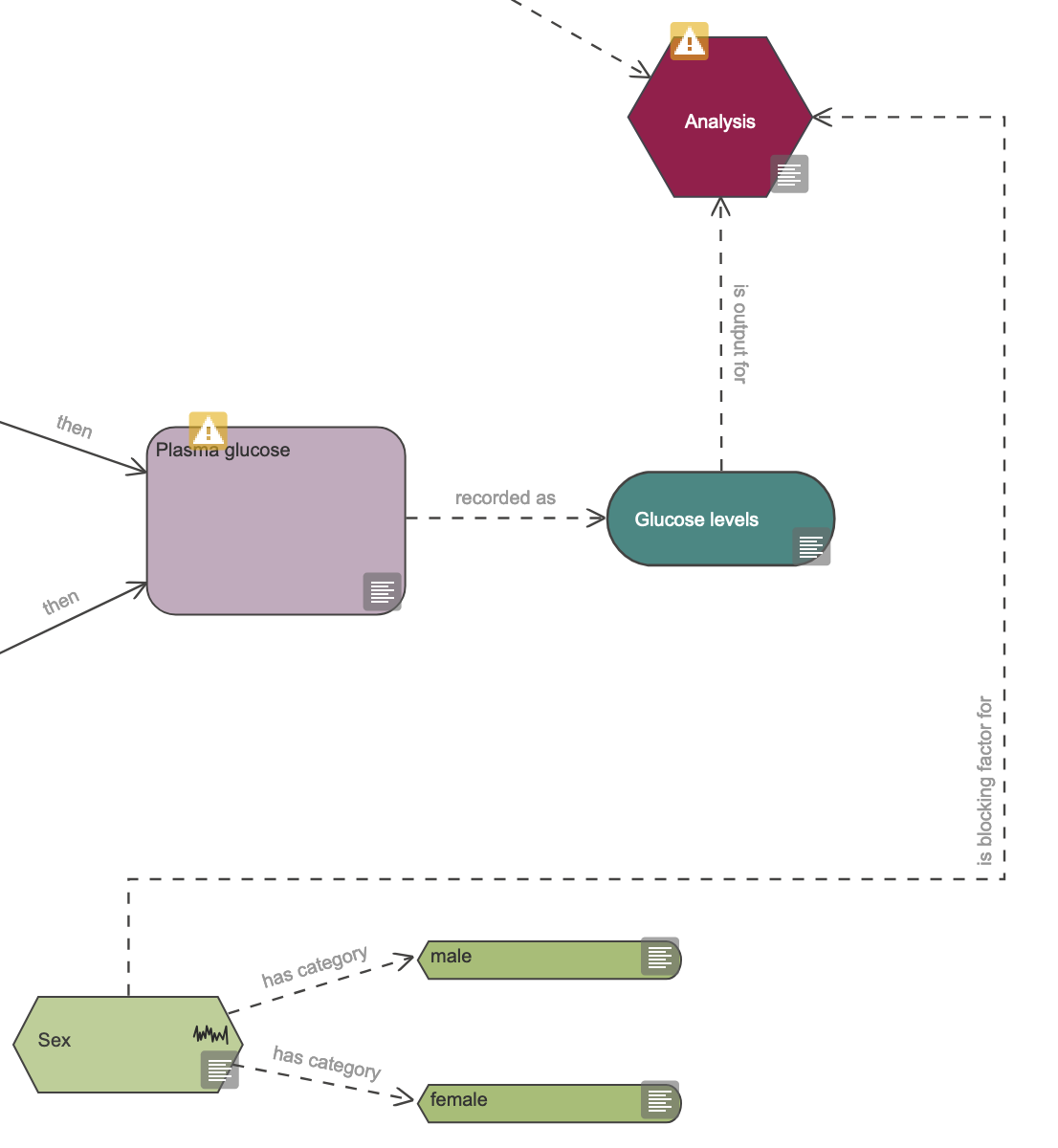

- Use the green lozenge icon in the Nuisance variable icon panel to create two new Variable category nodes. Label one as “male” and the other as “female” (Figure 18.9)

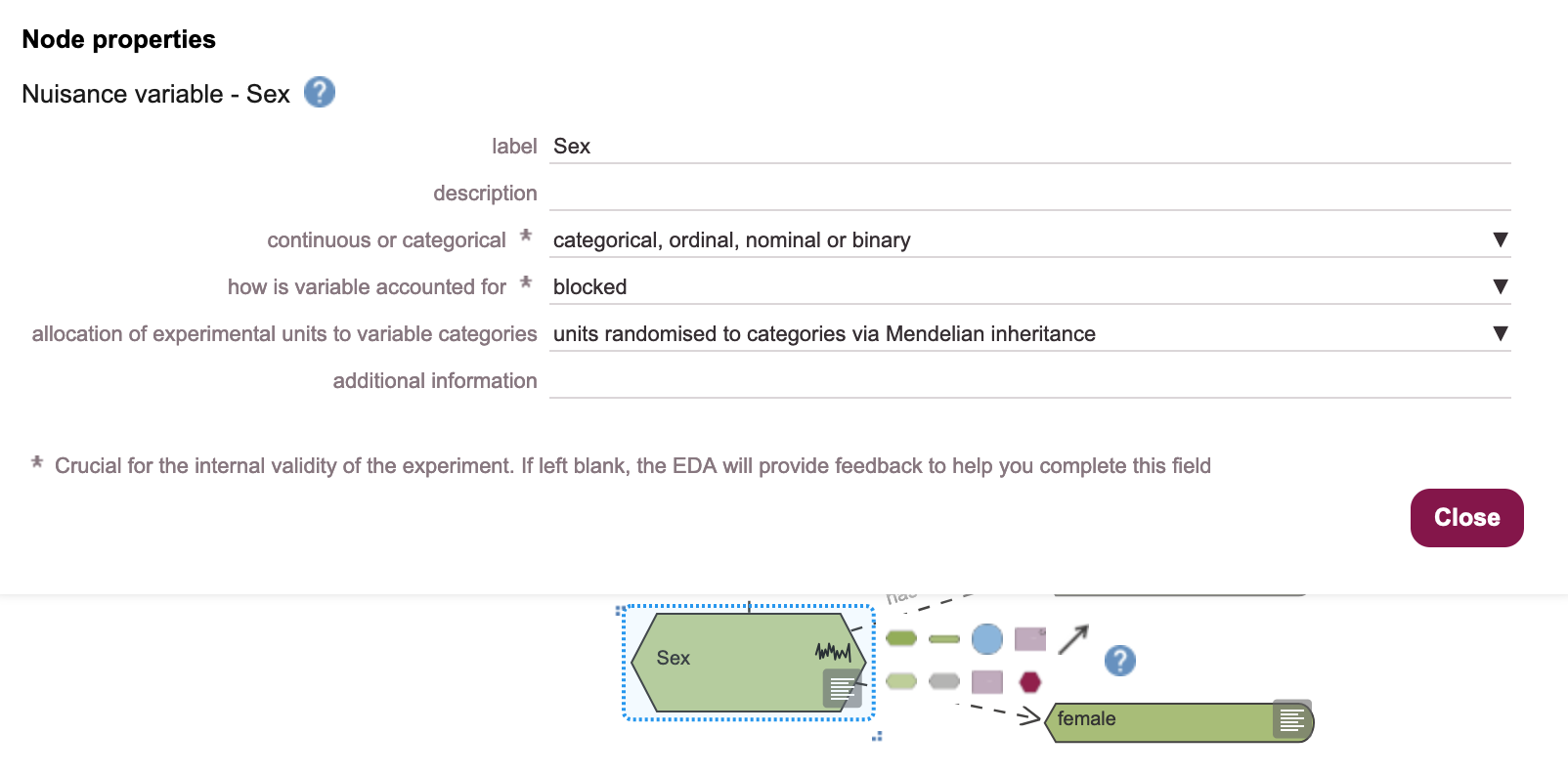

- Click on the Node properties icon on the Nuisance variable, and: set continuous or categorical to “categorical, ordinal, nominal, or binary” (sex is a categorical variable); set how is variable accounted for to “blocked” (this is how we are choosing to mitigate the effect); and set allocation of experimental units to experimental categories to “units randomised to categories via Mendelian inheritance” (this reflects that we, as experimenters, are not deciding whether animals are male or female) (Figure 18.10). Click on

Closeto dismiss the dialogue box.

18.2.4 Link sex to analysis as a blocking factor

Blocking factors describe subgroups of experimental results, divided by any source of variability or condition that might influence the measured outcome. Clearly, sex is one such factor (the response of an individual animal may vary depending on whether the animal is male or female), but we should always take care to identify and mitigate for any such sources of variability, in the way we conduct our experiments. Some possible blocking factors might include:

- the cage or room that individuals are housed in (there may be differences between locales that influence outcome)

- the time of day that measurements are made (animals may be diurnal, and respond differently in the morning and evening)

- the experimenter or handler’s identity (an inexperienced handler may cause stress in animals, and an experienced handler might not, affecting the subject’s response)

It is the responsibility of the researchers to identify any factors that might influence the study, and to mitigate for their effects.

If we are able to mitigate the effects of nuisance variables, either statistically or by revising the conduct or design of the experiment, then we are more likely to detect the true effect of the variable we are interested in.

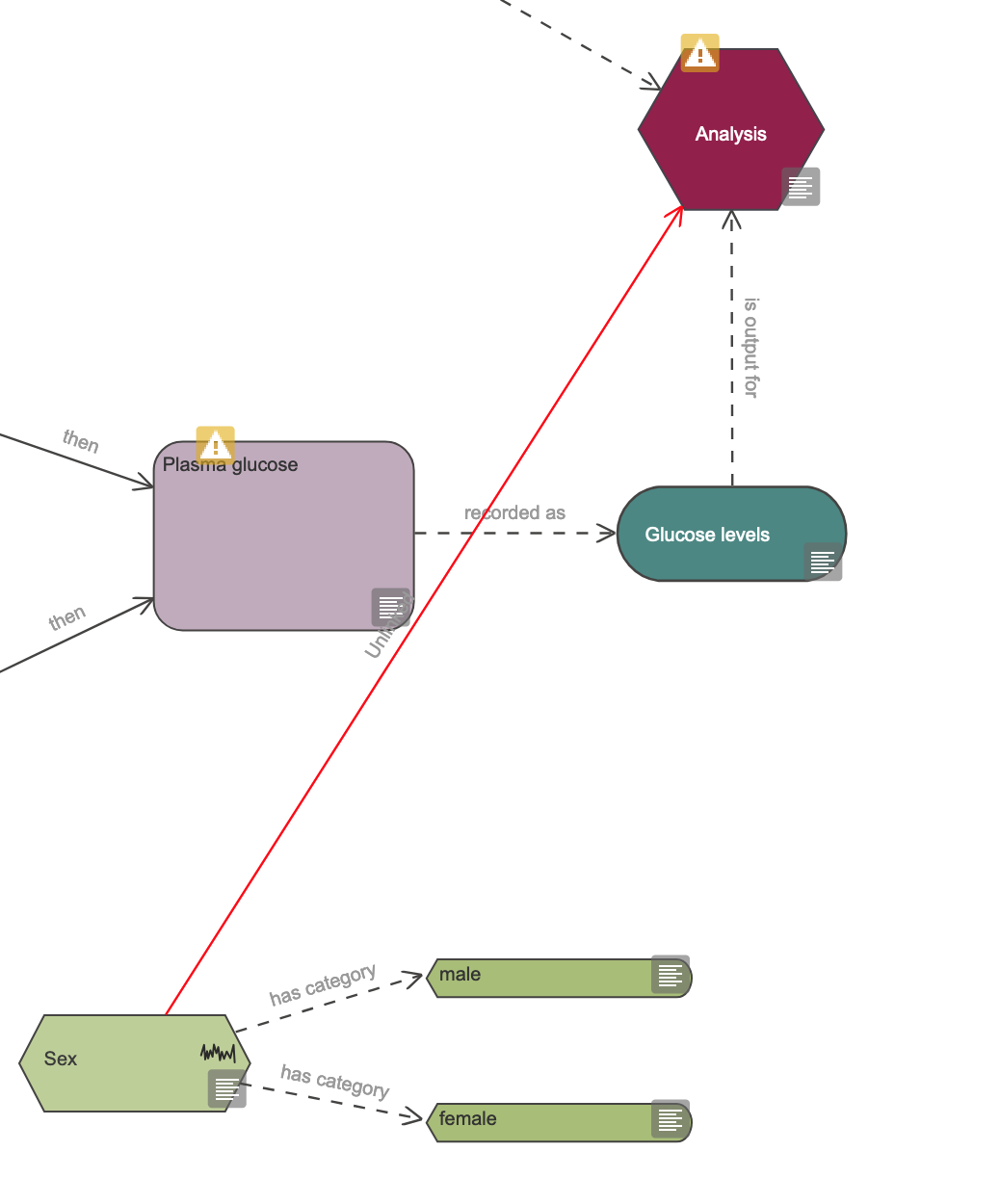

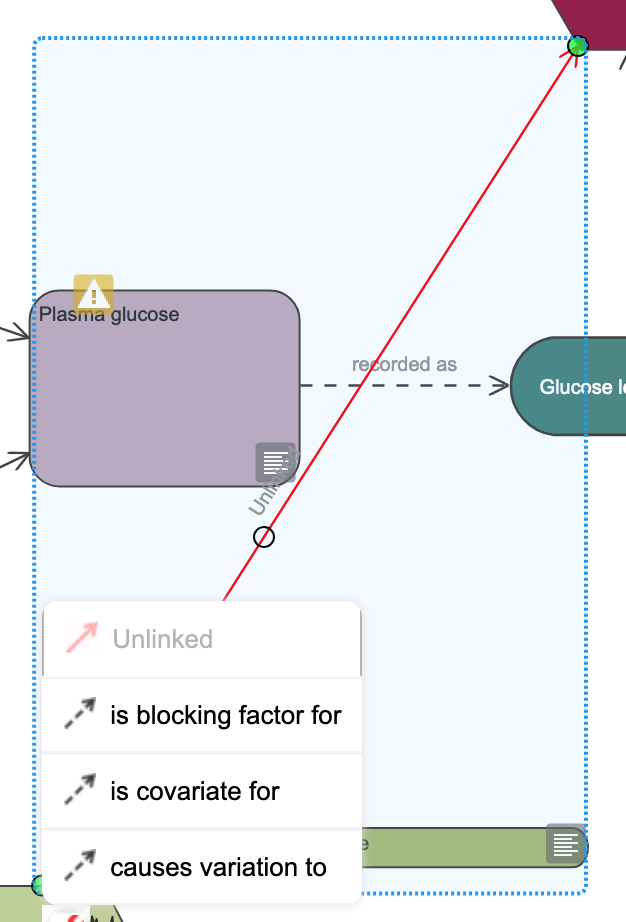

- Click on the arrow in the Nuisance variable icon panel, and drag it onto the Analysis node, to link them (Figure 18.11). To begin with, this arrow is red, to indicate that we have not specified the kind of relationship between this variable and the analysis.

- Click on the arrow, and hover the mouse pointer over the red spanner icon, to see the context menu. This offers options for the kind of relationship that the nuisance variable might have with the analysis (Figure 18.12).

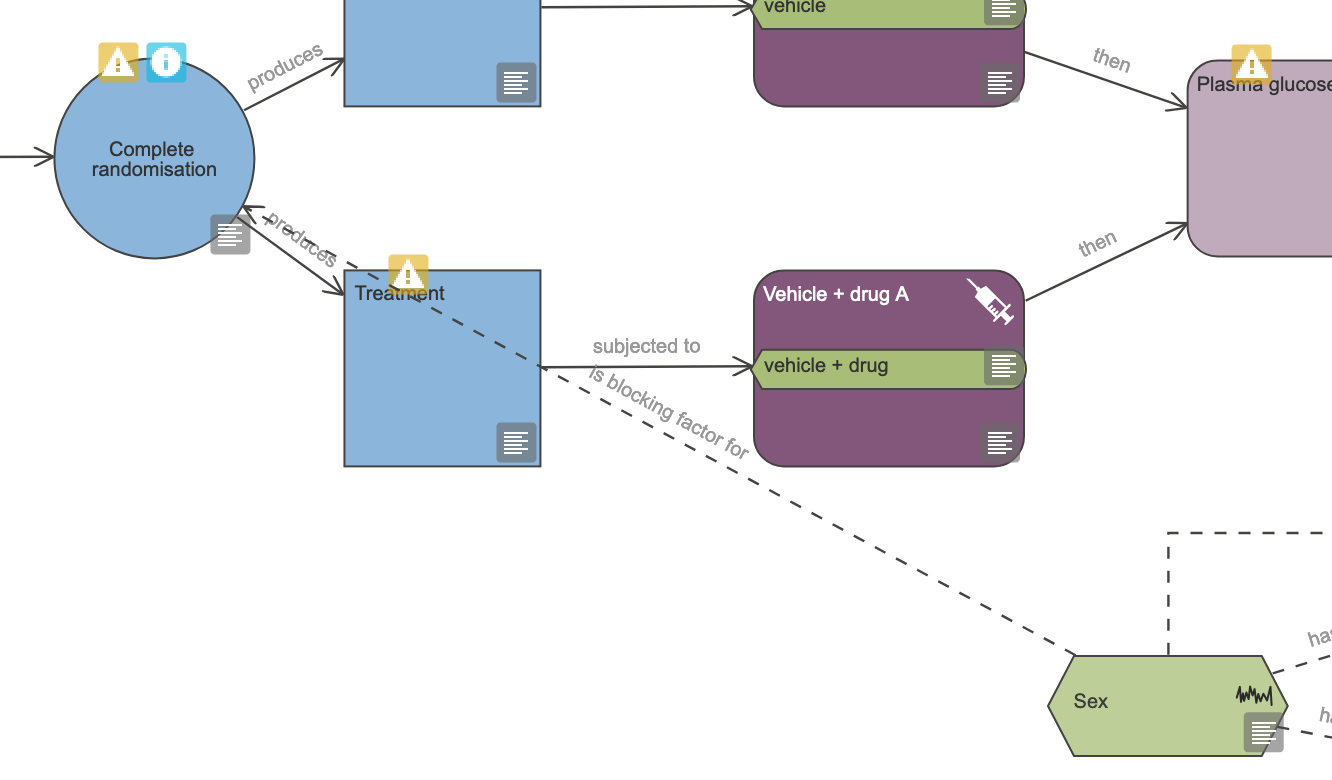

- Click on “is blocking factor for” in the context menu, to set the relationship. The arrow will change format from red, to grey dashes (Figure 18.13).

- Use the circles on the “is blocking factor for” linking arrow to reroute the arrow around the Outcome measure node, to improve readability (Figure 18.14).

18.2.5 Link sex to subject allocation

For a valid experimental design we must include blocking factors in the randomisation process of adding subjects to experimental groups. This ensures that each individual has an equal chance of receiving each treatment allocated to the block. We need to make sure that this is accounted for in the diagram.

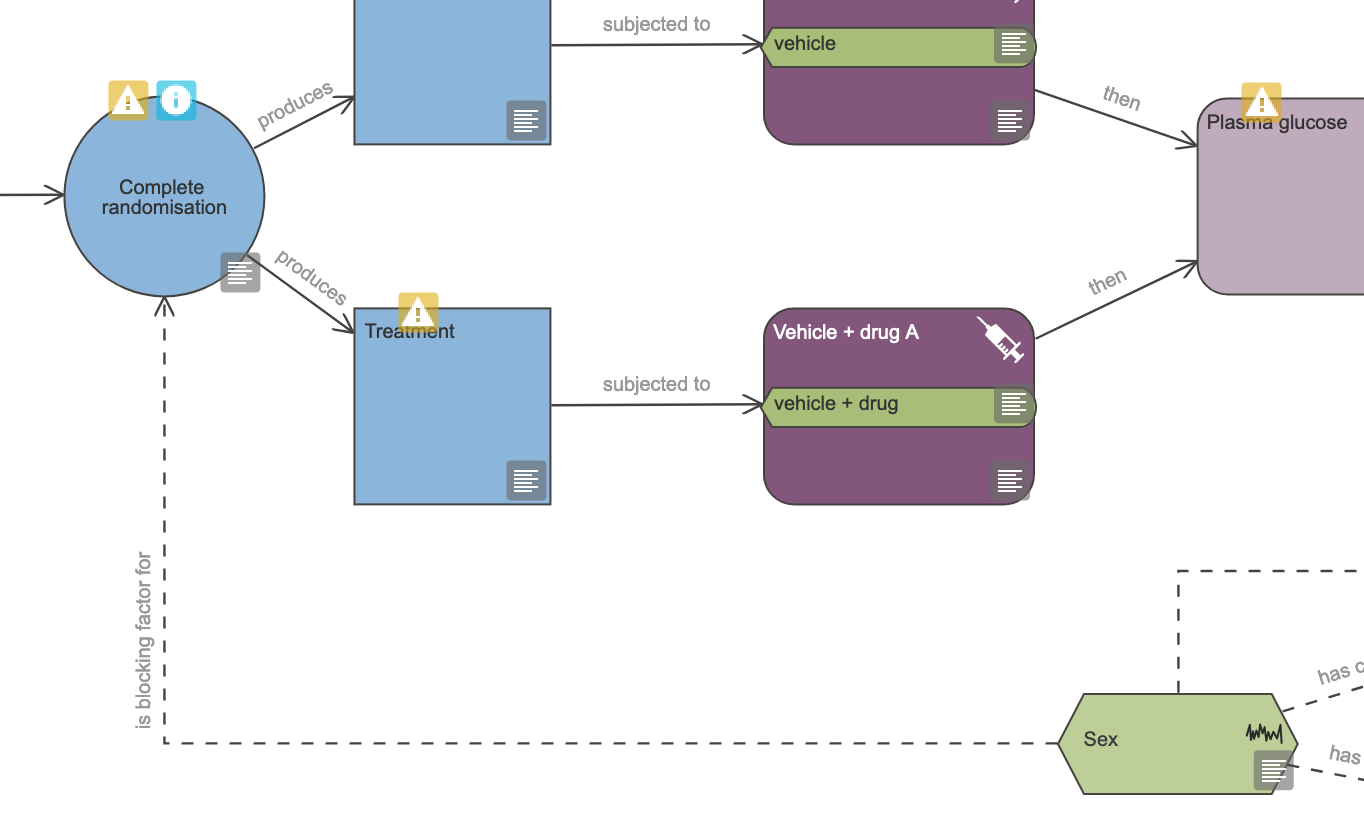

In the context of this experiment, we need to ensure that equal numbers of males and females are assigned to the Control (vehicle only) and Treatment (vehicle plus drug A) groups. This is referred to as “randomisation within blocks”: males and females are equally likely to be assigned to either the Control or Treatment groups.

We will need to modify the stated randomisation strategy, to account for how we are randomising individuals to groups, to reflect that we are randomising within blocks.

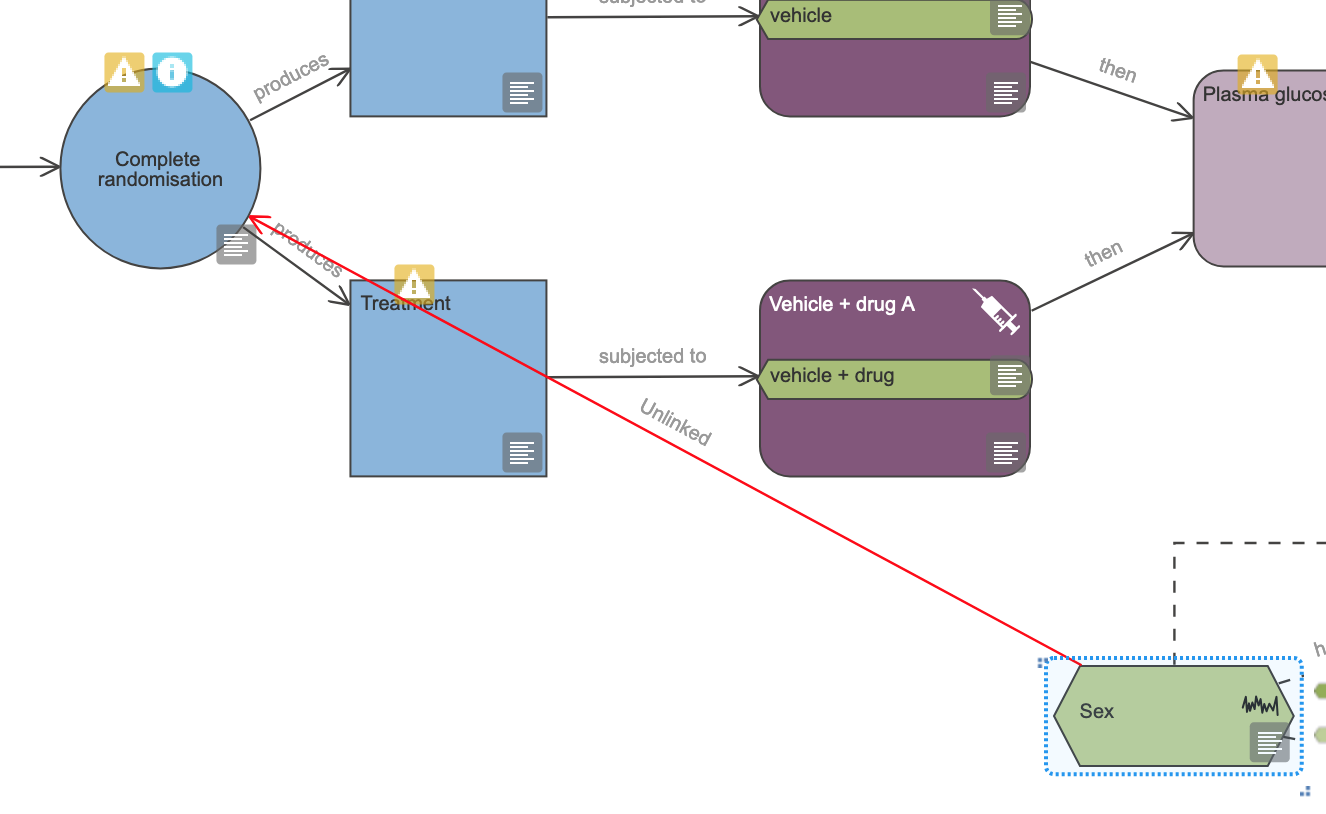

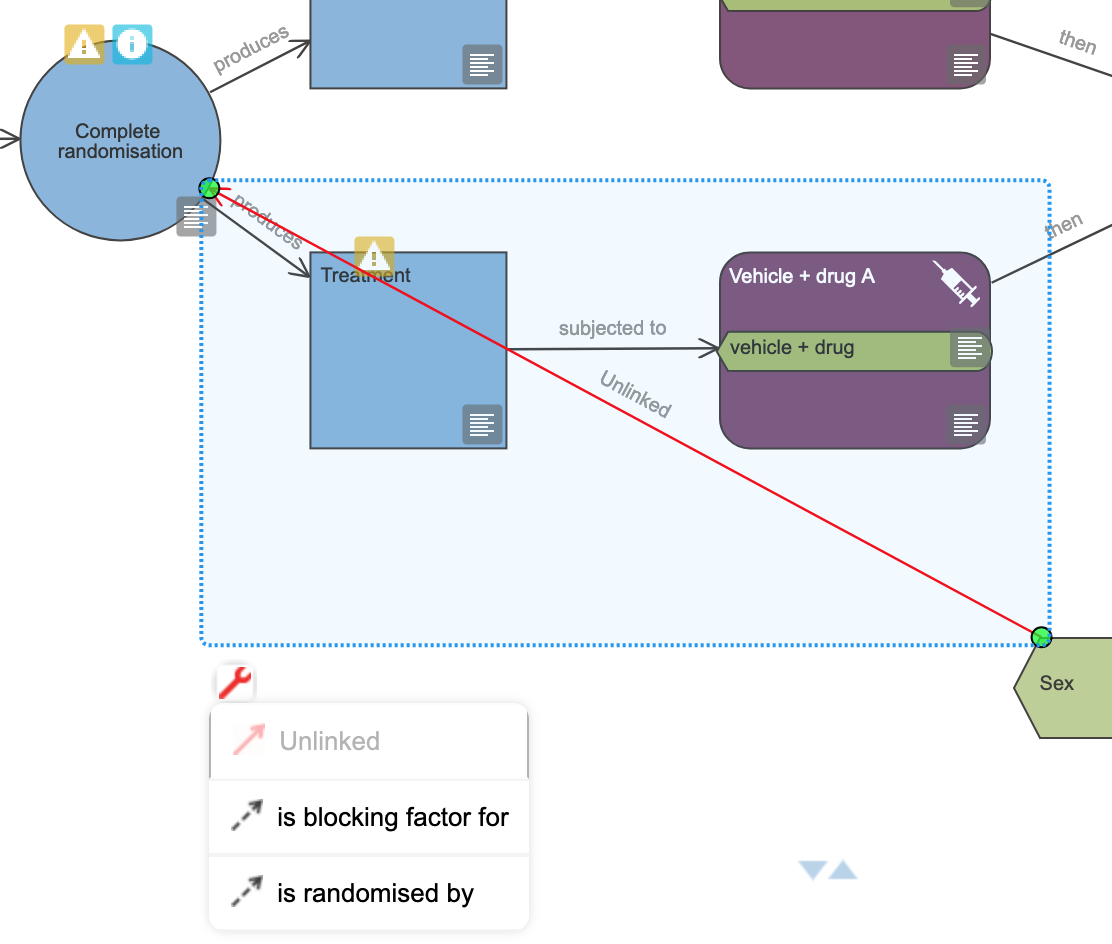

- Click on the arrow in the Nuisance variable icon panel, and drag it onto the Allocation node, to link them (Figure 18.15). As before,to begin with, this arrow is red, to indicate that we have not specified the kind of relationship between this variable and the allocation process.

- Click on the arrow, and hover the mouse pointer over the red spanner icon, to see the context menu. This offers options for the kind of relationship that the nuisance variable might have with the allocation process (Figure 18.16).

- Click on “is blocking factor for” in the context menu, to set the relationship. Like before, the arrow will change format from red, to grey dashes (Figure 18.17).

- Use the circles on the “is blocking factor for” linking arrow to reroute the arrow around the “Treatment” Group node, to improve readability (Figure 18.18).

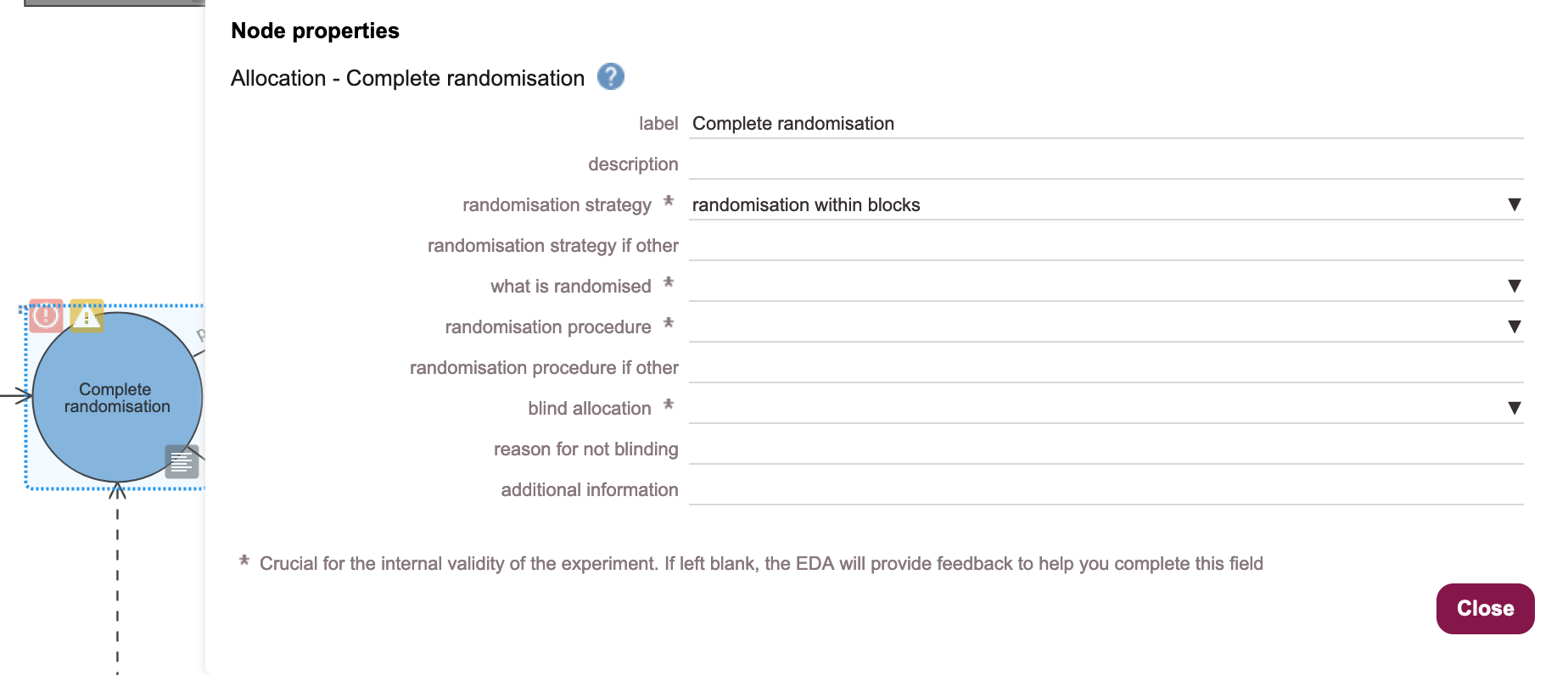

- Click on the Allocation node Node properties icon to bring up the dialogue box. Change the randomisation strategy field to “randomisation within blocks”, and click on

Closeto dismiss the dialogue box.

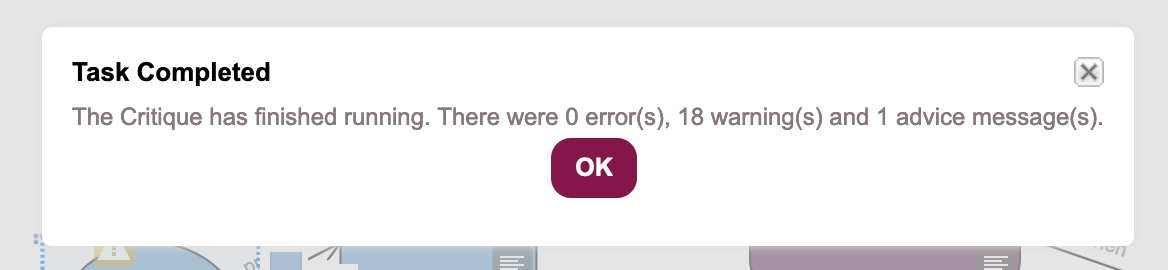

18.2.6 Rerun the Critique tool

- Use the

Toolsmenu and click onTools -> Critique - Read the critique output, then click on the

OKbutton to close.

No errors are reported, so we can now move on to ask EDA for suggestions around statistical analysis.

(What a Difference Sex and Gender Make: A Gender, Sex and Health Research Casebook Canadian Institutes of Health Research, ISBN: 978-1-100-19250-5)↩︎

A moment’s thought should reassure you that if it is believed there is no effect due to sex, then there is no statistical disadvantage to including both sexes in the experiment. Further reflection might suggest that if the treatment under study needs to be adminstered to determine its effectiveness at all, then it is curious to believe that we should already know enough about its efficacy in different sexes to assert that there is no difference.↩︎

This is not a new development. Methodological weaknesses in published experiments have been an ongoing concern for decades (Vorland (2021)).↩︎