4 Causal Models

4.1 What is a causal model?

A causal model is a system where if we change one variable in the model, we will also modify some variables in the model. The variable we change is called a cause and the variables that respond suffer the effects.

You will probably have correctly heard phrases like “correlation does not imply causation” in reference to the observation that just because you can identify two values apparently changing together, that doesn’t mean that the change in one value causes the other to change. The relationship might be the reverse of what you think (after all, an association between two sets values could run in either direction - the direction is not evident from the data alone), or it may be pure coincidence. There’s even a whole website dedicated to such spurious correlations.

It turns out that causation does not imply correlation either, but this is a complex topic that we don’t have time to get into in a single workshop about experimental design.

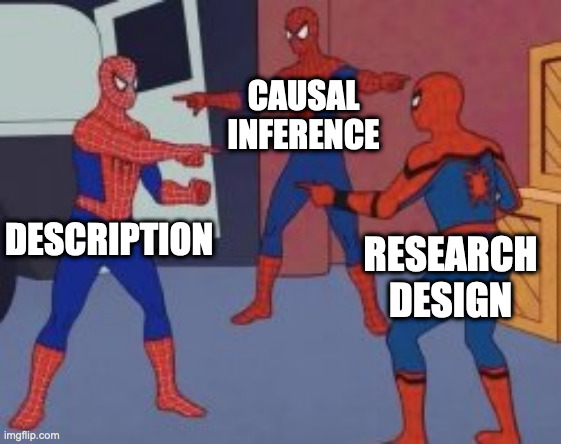

The statment “correlation does not imply causation” is often used dismissively to demean the role of statistics, but that’s unfair. It is possible to estimate causal effects using statistics, but all of the information about causal relationships comes from the researcher.

When we talk about causes and effects in the context of a statistical association (such as correlation) it is usually intended to mean one of two things:

- The estimate or prediction of the consequences of an intervention: e.g. if you administer a drug, there is an effect such as reduction in blood glucose concentration. In an experimental context you are often aiming to set up a system where a single intervention of interest (such as administration of a drug) is being made, and the consequences measured.

- The imputation of a missing observation - where you play “what if?” games by substituting values which you have not directly measured to see what changes in the system might result. You might measure the reduction of blood glucose concentration in response to a drug, and from this be able to calculate the amount of drug that was delivered. In general, this allows us to construct unobserved counterfactual outcomes, where we can imagine an outcome (lower blood glucose by 4mM) and work out what dose of drug to give to achieve it.

If you are aware of, or propose, a causal relationship you are expressing the belief that you can predict the consequences of an intervention.

For example, if you look out of the window and see trees swaying, and there is some wind, you know the two are connected because you intuitively understand that the wind is causing the trees to sway, not that the trees are moving and creating the wind.

But suppose you were an alien from another planet with no knowledge of the Earth, and simply measured windspeed and tree movement. You would find a correlation, but there would be only a statistical association. There would be nothing in the data itself to tell you which was the cause and which was the effect.

But you, a mere Earthling know the causal relationship and the nature of the intervention: wind makes trees sway. If you climbed into the tree and rocked it, you would not generate wind. But if you measured the amount by which a tree sways, you could make an estimate of the prevailing windspeed.

All information about causal relationships comes from the scientists’ understanding of the world or, more to the point, their understanding of the experimental system.

4.1.1 Your beliefs about the system are the causal model

The assumptions and beliefs you have that cause you to consider setting up your experiment are a kind of causal model.

For instance, if you believe that reaction times get slower when someone has drunk alcohol, then your causal model is that alcohol consumption causes change in reaction times.

You would design your experiment to enable measurements of alcohol consumption and reaction time to be measured, and you might look to find a statistical association. But if you did find a statistical association, your causal interpretation (e.g. that “reaction time slows with increasing alcohol dose”) would be the result of your beliefs about the experimental system, not a result of simply running statistical analysis on the dataset.